Pelvic pain is one of the most frequent complaints among females presenting to emergency departments. Rapid and accurate diagnosis is paramount for timely and appropriate management. Among the many imaging modalities available, ultrasound stands out as the primary tool for evaluating pelvic emergencies due to its noninvasive nature, accessibility, and ability to assess vascularity in real-time. This article provides an in-depth review of female pelvic ultrasound, focusing on its applications in common and rare pelvic emergencies. It covers essential sonographic techniques, key pathologies, and critical imaging signs that radiology trainees and practicing radiologists must recognize to optimize patient outcomes.

Table of Contents

- Ultrasound Techniques for Pelvic Emergencies

- Ectopic Pregnancy: The Most Critical Pelvic Emergency

- Adnexal Torsion: A Vascular Emergency

- Ovarian Cysts and Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID)

- Intrauterine Contraceptive Device (IUCD) Assessment

- Other Causes of Pelvic Pain in Ultrasound Evaluation

- High-Yield Imaging Signs Summary

- FAQ: Female Pelvic Ultrasound in Emergency Settings

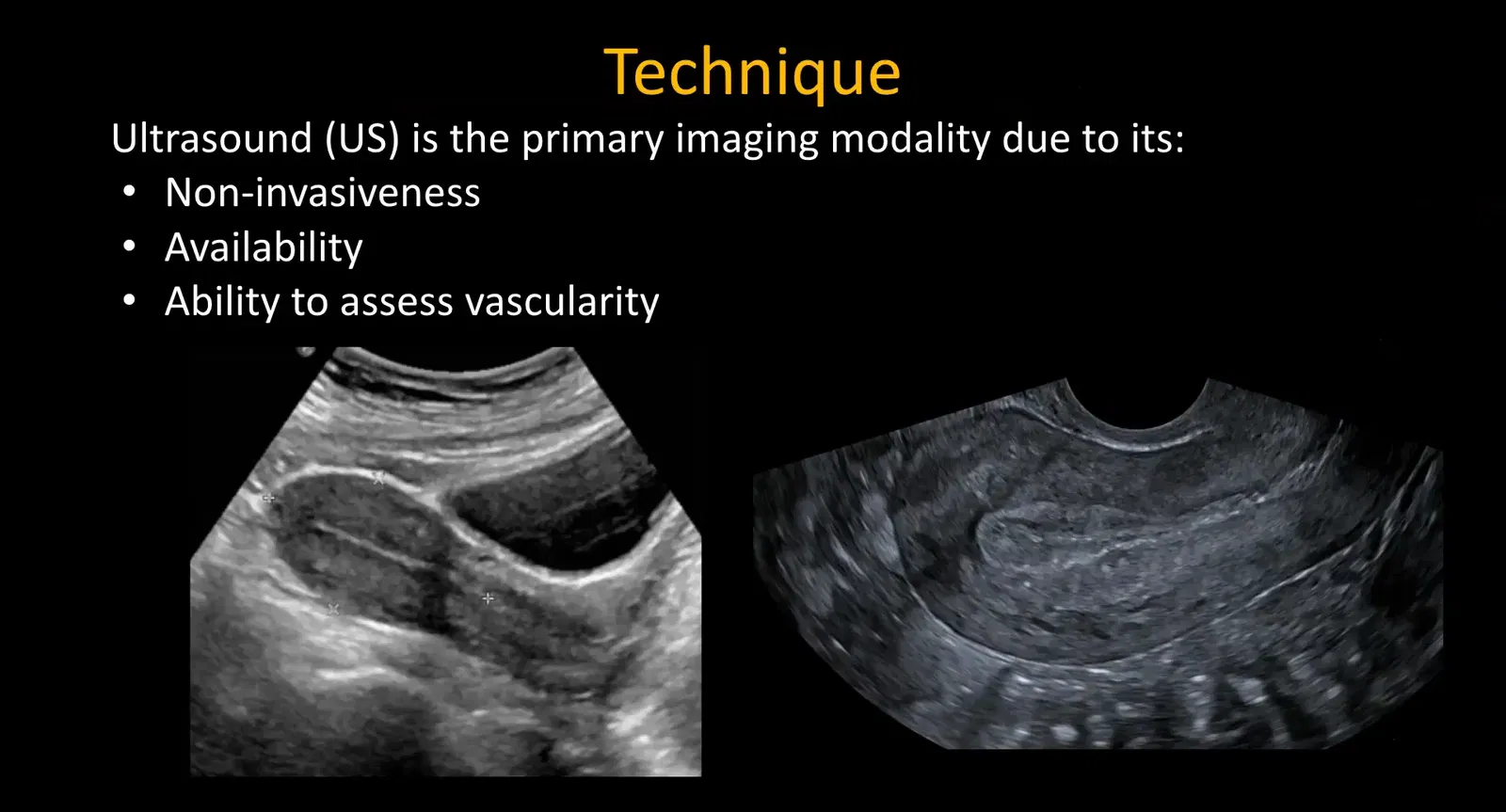

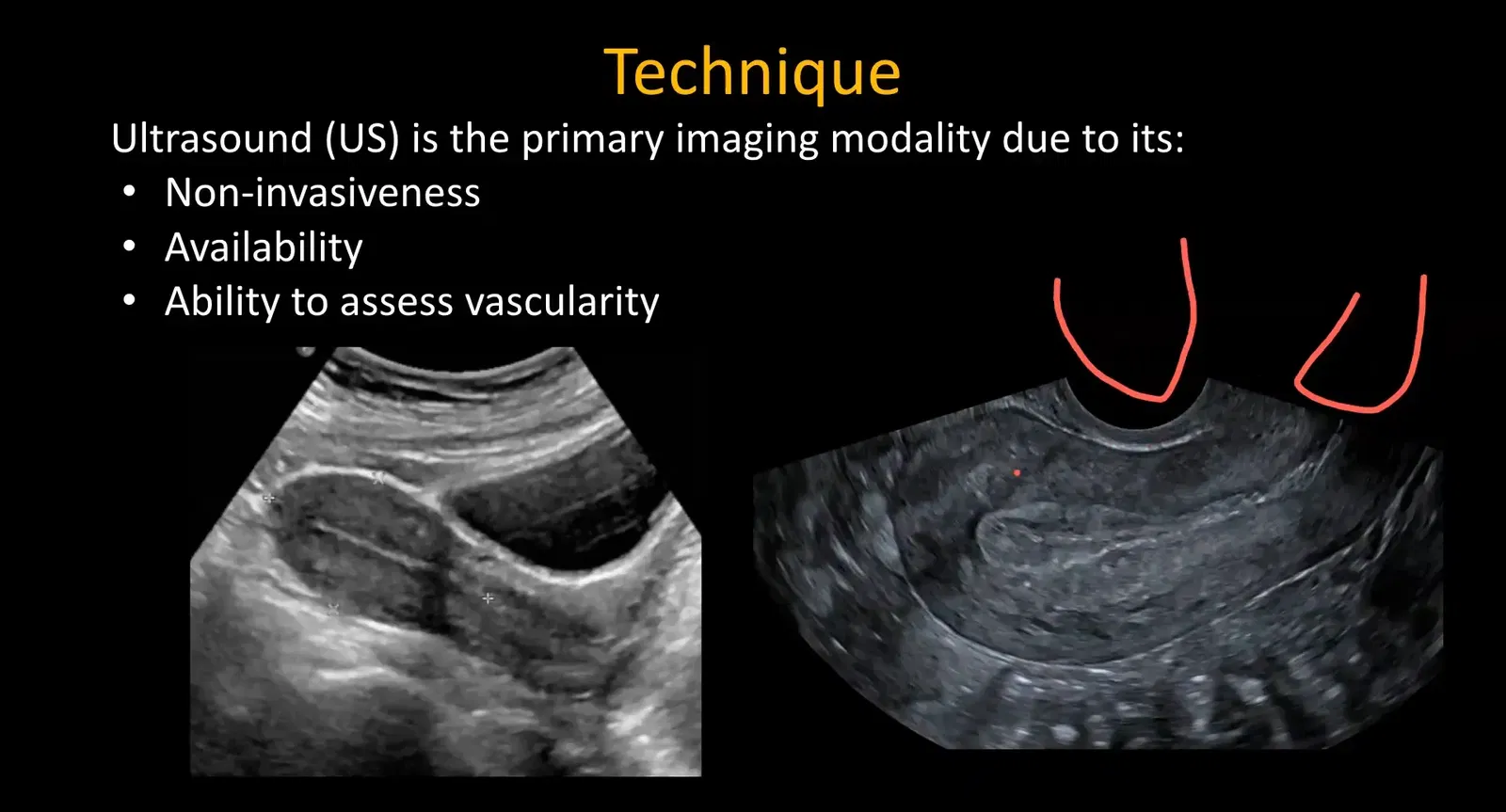

Ultrasound Techniques for Pelvic Emergencies

Ultrasound evaluation of the female pelvis in emergencies usually begins with a transabdominal pelvic ultrasound. This is performed with a full bladder to use the bladder as an acoustic window, enhancing visualization of pelvic organs. The transabdominal approach also allows simultaneous screening for renal and bladder abnormalities, which can present with pelvic pain, such as ureteric calculi or bladder pathology. Additionally, since pelvic pain can mimic or be caused by other abdominal emergencies like acute appendicitis, the transabdominal scan often includes an assessment of the right lower quadrant and kidneys.

Following the transabdominal exam, a transvaginal ultrasound is generally performed for superior resolution and detailed evaluation of pelvic structures. The transvaginal probe is inserted into the vagina, providing a sagittal view oriented towards the uterus and adnexa. This approach offers better spatial resolution and is particularly valuable for detecting smaller lesions or subtle changes within the uterus, ovaries, and adnexa.

For radiology trainees, hands-on experience with transvaginal scanning is crucial to developing anatomical orientation and confidence in interpreting sonographic images. Practicing on multiple patients during ultrasound rotations helps build familiarity with normal and pathological pelvic anatomy.

Ectopic Pregnancy: The Most Critical Pelvic Emergency

Ectopic pregnancy is a leading cause of maternal mortality in the first trimester and is a critical diagnosis to identify promptly. It accounts for approximately 6% to 16% of pregnancies presenting with pelvic pain or vaginal bleeding. Early diagnosis before rupture can allow for medical management, avoiding surgical intervention and significant morbidity.

Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy include tubal abnormalities, prior ectopic pregnancies, and history of pregnancy complications. The majority of ectopic pregnancies (~95%) occur in the fallopian tubes (tubal pregnancies), while ovarian or abdominal ectopics are rare.

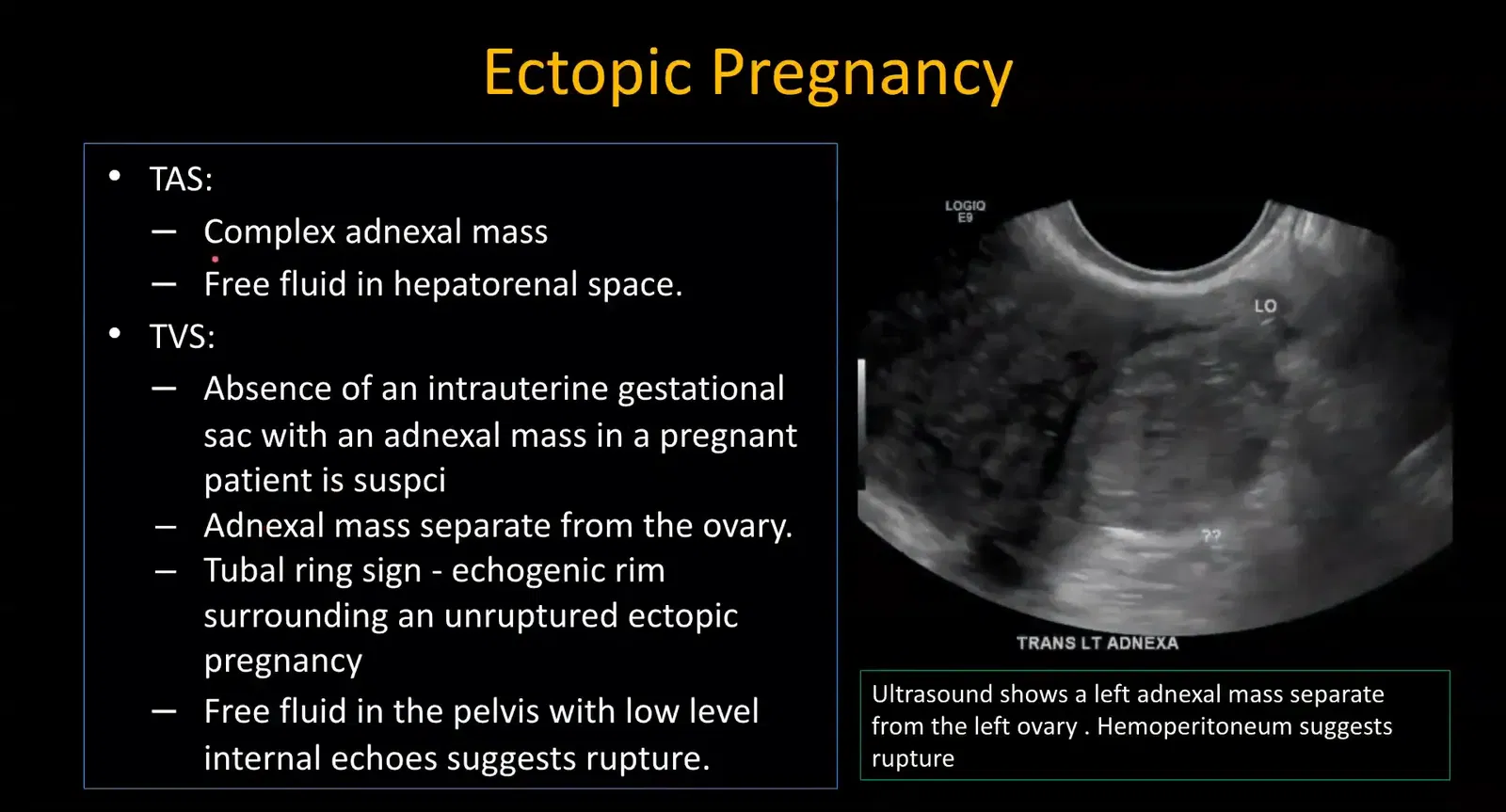

Sonographic Findings in Ectopic Pregnancy

On ultrasound, ectopic pregnancy is suspected when a pregnant patient (confirmed by positive beta-hCG or urine pregnancy test) shows absence of an intrauterine gestational sac coupled with an adnexal mass separate from the ovary.

Other important findings include:

- Complex adnexal mass: Heterogeneous echogenicity representing the ectopic gestation.

- Free fluid in the pelvis and hepatorenal space: Presence of low-level internal echoes within free fluid suggests hemoperitoneum, indicative of rupture and hemorrhage.

- Tubal ring sign: An echogenic rim surrounding an unruptured ectopic pregnancy, though not always visible.

Because fluid can accumulate in the hepatorenal recess only after significant bleeding, finding free fluid here indicates a potentially life-threatening rupture. Therefore, always assess the hepatorenal space during pelvic ultrasound for free fluid.

Interstitial Ectopic Pregnancy

Interstitial pregnancies occur in the interstitial portion of the fallopian tube that traverses the myometrium. This subtype is rare but carries higher morbidity and mortality due to delayed diagnosis and risk of massive hemorrhage.

Sonographic clues include:

- Thin myometrium (<5 mm) surrounding the gestational sac: Suggests an eccentric implantation site.

- Interstitial line sign: A thin echogenic line extending from the endometrium to the ectopic sac.

These signs can be subtle and not always present. Follow-up imaging and clinical correlation are often necessary, as some cases may continue as normal pregnancies despite eccentric implantation.

Adnexal Torsion: A Vascular Emergency

Adnexal torsion involves twisting of the ovarian or adnexal vascular pedicle, leading to ischemia. It is a gynecological emergency requiring prompt diagnosis to salvage ovarian function.

Clinical Presentation and Epidemiology

Patients typically present with sudden, severe unilateral pelvic pain. Torsion is more common in younger women due to greater ovarian mobility. In older patients, torsion usually occurs in the presence of an adnexal mass such as ovarian cysts, especially dermoid cysts. Endometriomas and ovarian malignancies rarely cause torsion due to adhesions tethering the ovary.

The right ovary is more frequently affected than the left, as the sigmoid colon protects the left adnexa from torsion.

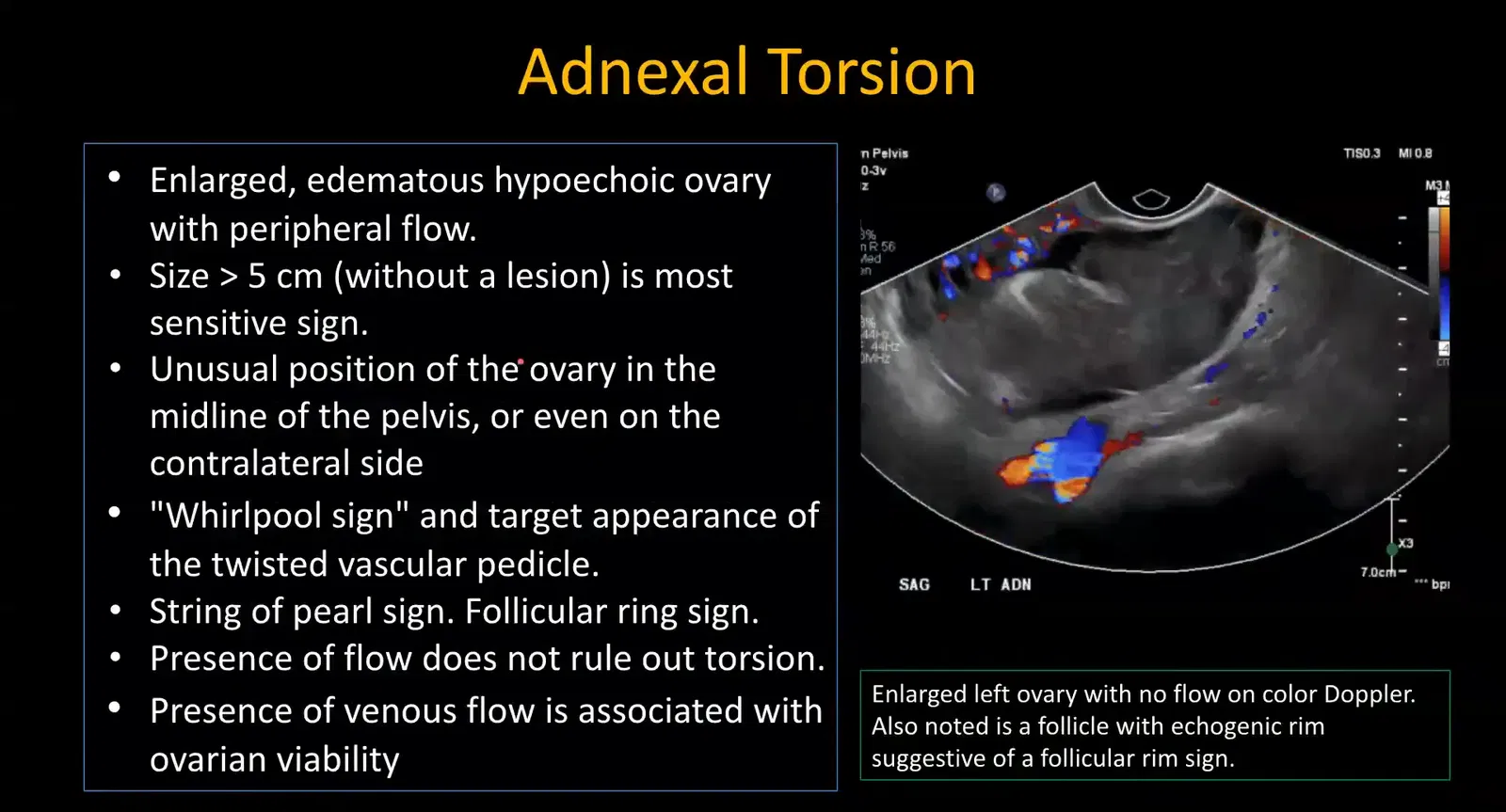

Ultrasound Features of Adnexal Torsion

Key sonographic signs include:

- Enlarged ovary: Typically >5 cm (normal ovary size is 3-4 cm), due to edema and venous congestion.

- Ovarian edema: Follicles displaced peripherally, producing the string of pearls sign. Note that this appearance can also be seen in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), so clinical context is essential.

- Follicular ring sign: Echogenic rim around follicles due to edema and hemorrhage, fairly specific for torsion.

- Unusual ovary position: Displacement toward the midline or contralateral side.

- Whirlpool sign: Visualization of twisted vascular pedicle; challenging on ultrasound but can be detected on Doppler or CT.

While Doppler ultrasound is valuable, presence of arterial flow does not exclude torsion due to dual arterial supply from ovarian and uterine arteries. Absence of venous flow is an earlier and more sensitive sign. Always document both arterial and venous waveforms during Doppler evaluation.

Loss of venous flow correlates with increased risk of ovarian infarction, but persistent venous flow suggests potential ovarian viability, guiding surgical management.

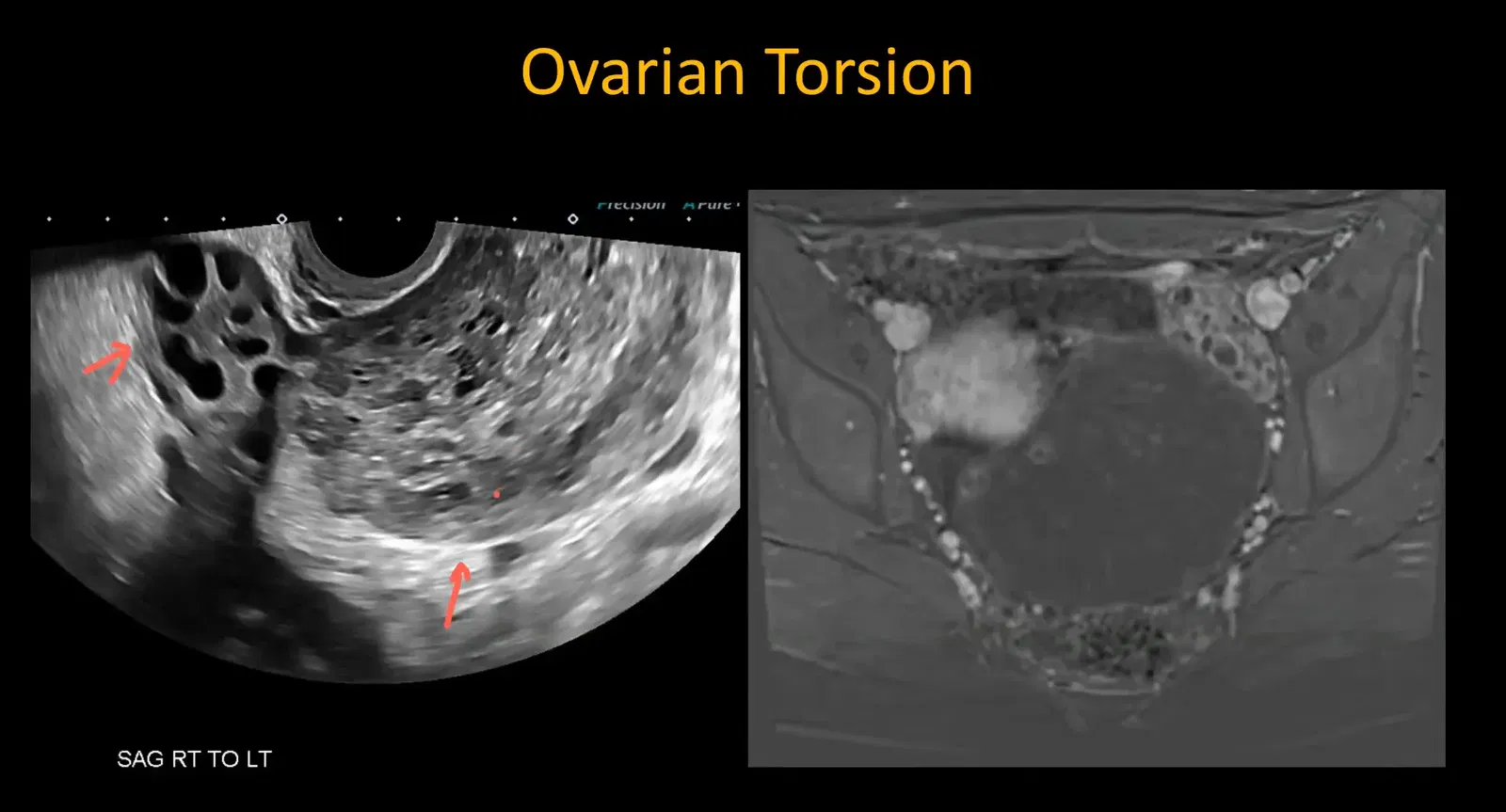

Case Illustration

A young female presented with left-sided pelvic pain. Ultrasound showed an enlarged left ovary with minimal Doppler flow. The ovary was displaced medially, and multiple follicles exhibited the follicular ring sign. MRI confirmed the diagnosis with lack of enhancement in the twisted ovary.

Ovarian Cysts and Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID)

Ovarian Cysts

Ovarian cysts are common, often asymptomatic lesions that may cause pelvic pain if large, hemorrhagic, or ruptured.

Sonographic features of hemorrhagic cysts include:

- Lacelike or spider-web internal echoes: Representing fibrin strands.

- Fluid-fluid levels and fluid debris: From clot retraction.

- Absent internal vascular flow: Differentiates hemorrhagic cysts from solid masses.

Ruptured cysts may present with complex free fluid and irregular cyst margins.

Mittelschmerz

A less common cause of acute pelvic pain is ovulation pain or Mittelschmerz. Ultrasound may show a dominant follicle with crenulated margins and minimal surrounding fluid.

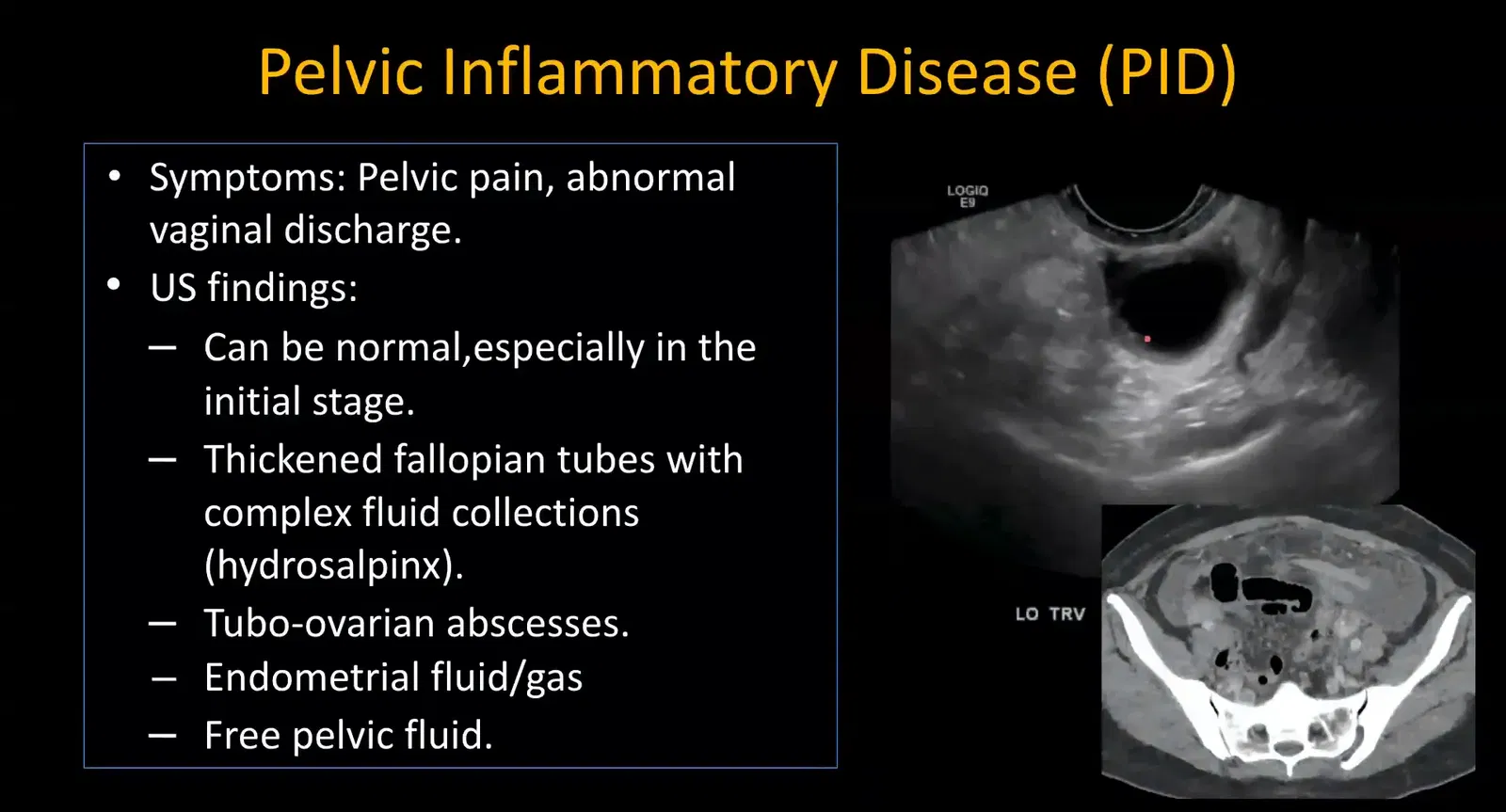

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID)

PID commonly affects younger women and may initially be difficult to detect on imaging. Advanced cases show:

- Dilated fallopian tubes: Hydrosalpinx or pyosalpinx with thickened walls.

- Tubo-ovarian abscess: Complex adnexal masses with internal debris and septations.

It is critical to differentiate tubo-ovarian abscess from other pelvic abscesses such as ruptured appendicitis or complicated diverticulitis. When adnexal structures are not clearly separable from abscesses, cross-sectional imaging like CT is recommended for precise localization.

Intrauterine Contraceptive Device (IUCD) Assessment

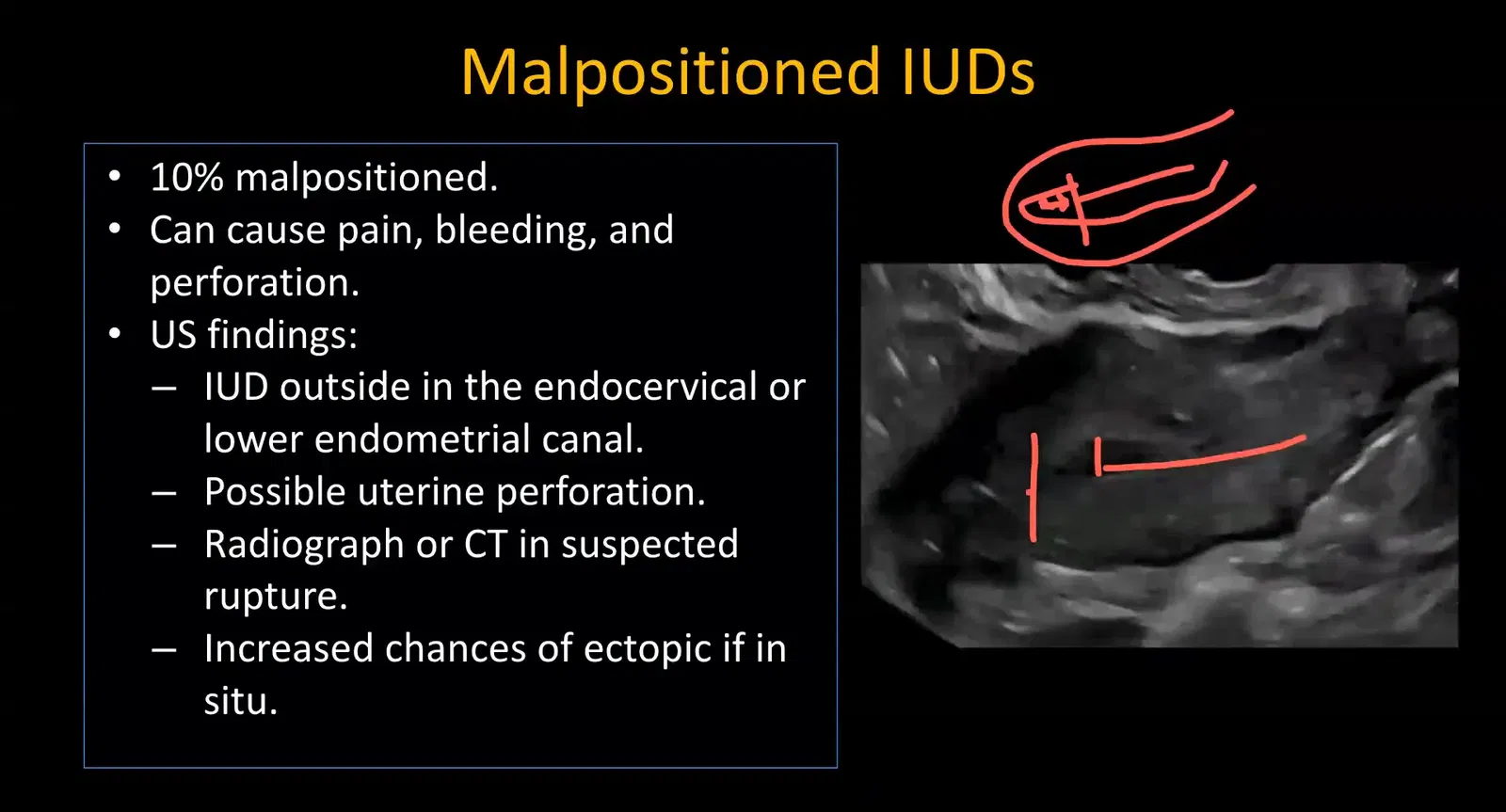

Most IUCDs are well positioned and asymptomatic, but about 10% can be malpositioned, causing pain, bleeding, or rarely perforation.

Newer IUCDs are made of pliable materials, reducing the risk of uterine wall perforation. When ultrasound shows IUCD limbs indenting the myometrium without clear perforation, use the term indenting rather than perforating.

Normal IUCD Position

The vertical limb of the IUCD should be located approximately 5 to 6 mm from the top of the fundal endometrium.

Malpositioned IUCD

Malposition is suspected when the IUCD limbs are asymmetrical or extend towards the endocervix and the normal T-shaped configuration is lost.

If the IUCD is not visualized on ultrasound and the patient denies expulsion, radiographs should be performed to localize the device. If found outside the uterine cavity, CT is the next step to evaluate for perforation.

Other Causes of Pelvic Pain in Ultrasound Evaluation

Chronic Conditions with Acute Presentations

Common chronic pelvic pathologies such as uterine fibroids and endometriomas can rarely present with acute symptoms due to degeneration, torsion, or rupture.

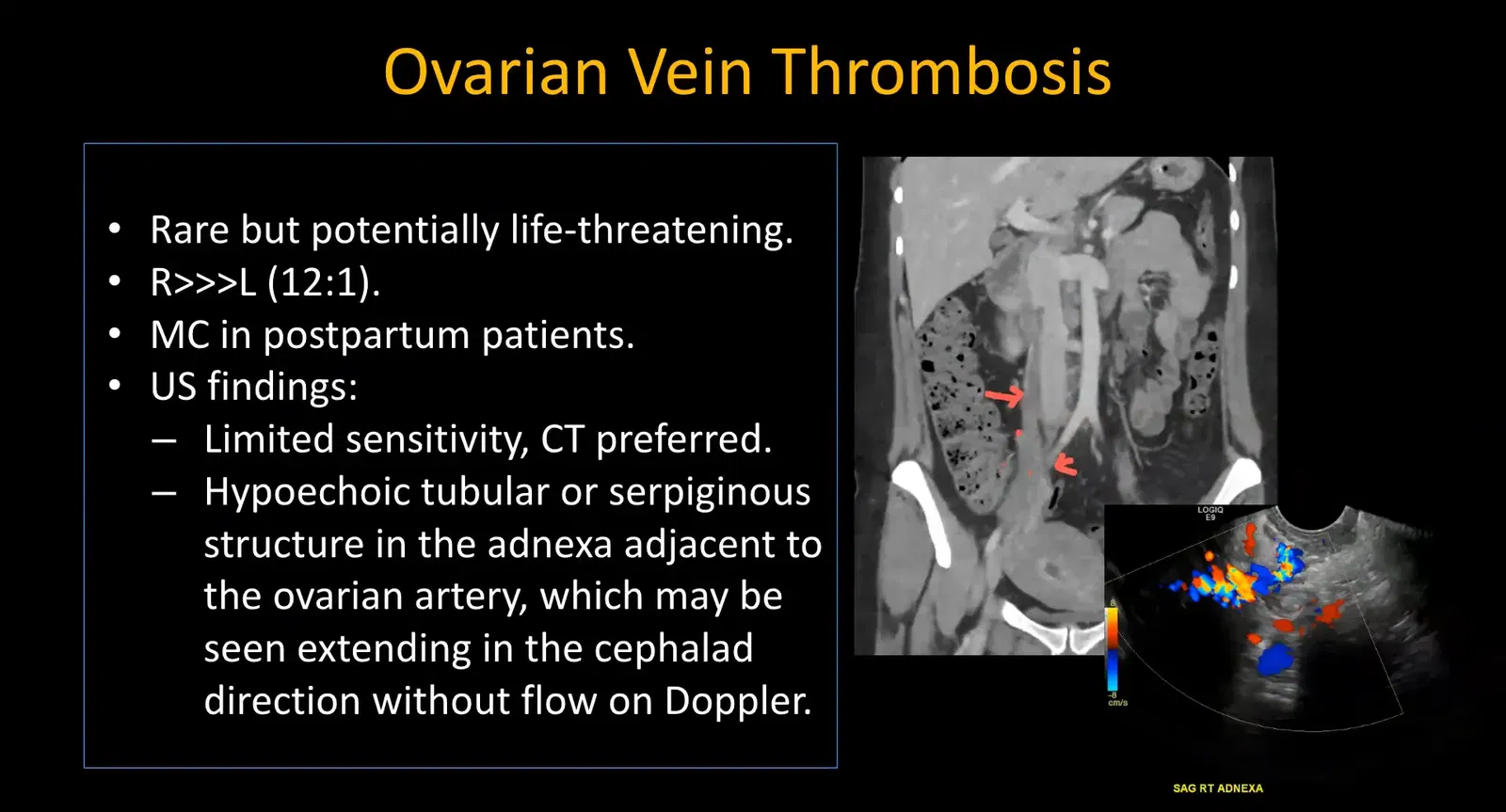

Ovarian Vein Thrombosis

A rare but important diagnosis, ovarian vein thrombosis (OVT) mostly occurs in the postpartum period. Ultrasound visualization of thrombosed adnexal vessels is challenging due to limited views of adnexal veins.

CT imaging is more sensitive, showing an enlarged ovarian vein with a filling defect. Retrospective review of ultrasound may reveal a cord-like structure representing the thrombosed vein.

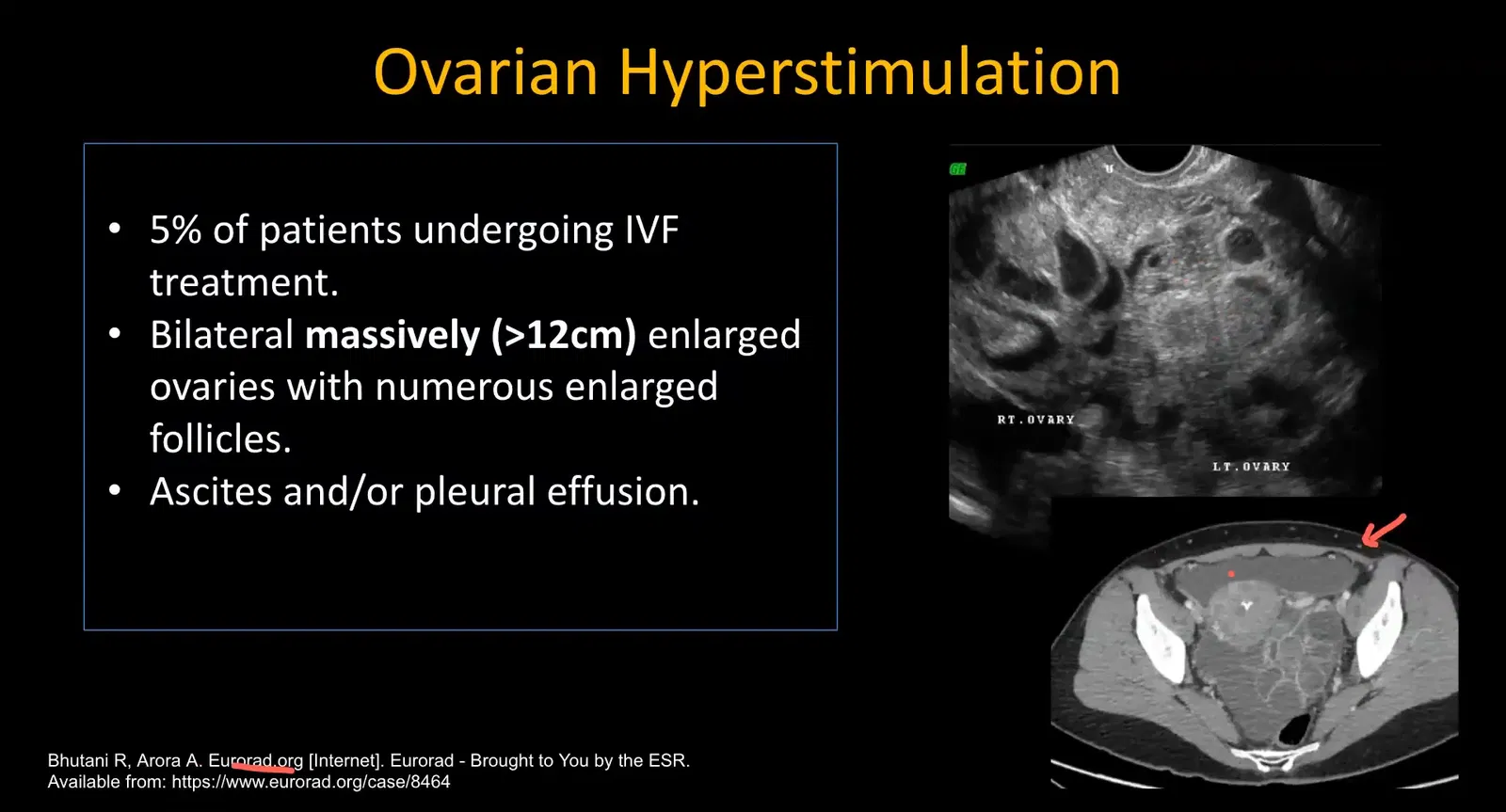

Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome (OHSS)

OHSS is typically seen in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF). Both ovaries become massively enlarged (>12 cm), with multiple cysts and associated free fluid in the abdomen and pleural spaces.

While ultrasound is the modality of choice, sometimes CT is performed, which shows bulky ovaries and ascites.

Other Common Pelvic Pain Etiologies

Besides gynecological causes, pelvic pain may arise from urological or gastrointestinal sources such as:

- Ureterovesical junction (UVJ) or lower ureteric calculi

- Acute appendicitis

Hence, pelvic ultrasound protocols often include kidney scanning and right lower quadrant evaluation when clinically indicated.

High-Yield Imaging Signs Summary

| Pathology | Key Ultrasound Findings | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ectopic Pregnancy | Absent intrauterine gestational sac, adnexal mass separate from ovary, free fluid with low-level echoes | Assess hepatorenal space for hemoperitoneum |

| Interstitial Pregnancy | Thin myometrium (<5 mm) around sac, interstitial line sign | Challenging diagnosis; follow-up advised |

| Adnexal Torsion | Enlarged ovary >5 cm, peripheral displaced follicles (string of pearls), follicular ring sign, absent venous flow | Arterial flow may persist; document arterial and venous Doppler |

| Hemorrhagic Ovarian Cyst | Lacelike internal echoes, fluid debris, no internal flow, crenulated margins if ruptured | Common cause of acute pelvic pain |

| Pelvic Inflammatory Disease | Dilated tubes with thickened walls, tubo-ovarian abscess | Differential includes ruptured appendicitis/diverticulitis abscess |

| Malpositioned IUCD | Asymmetrical limbs, limbs indenting myometrium, absent device on ultrasound | Confirm with radiographs and CT if suspected perforation |

| Ovarian Vein Thrombosis | Cord-like structure in adnexa, dilated ovarian vein with filling defect on CT | Most common postpartum; difficult on ultrasound |

| Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome | Massively enlarged ovaries >12 cm, free fluid in abdomen and pleural spaces | Usually post-IVF |

FAQ: Female Pelvic Ultrasound in Emergency Settings

Q1: Why is ultrasound preferred over other imaging modalities in pelvic emergencies?

Ultrasound is noninvasive, widely available, can be performed bedside, and allows real-time assessment of vascularity using Doppler. It avoids radiation and is cost-effective, making it ideal for rapid evaluation of female pelvic emergencies.

Q2: How do you differentiate between a ruptured ectopic pregnancy and a hemorrhagic ovarian cyst on ultrasound?

Both may present with free fluid and adnexal masses. Ruptured ectopic pregnancy typically shows an absent intrauterine gestational sac with an adnexal mass separate from the ovary and complex free fluid in the pelvis and hepatorenal space. Hemorrhagic cysts have characteristic internal lace-like echoes, no intrauterine pregnancy, and usually no significant free fluid unless ruptured.

Q3: Can Doppler ultrasound exclude adnexal torsion if blood flow is present?

No. Presence of arterial flow does not exclude torsion due to dual arterial supply. Absence of venous flow is more sensitive for torsion. Always document both arterial and venous waveforms.

Q4: What is the significance of the follicular ring sign in ovarian torsion?

The follicular ring sign is an echogenic rim around ovarian follicles caused by edema and hemorrhage, and it is fairly specific for ovarian torsion. Identification aids in diagnosis especially when combined with other signs like ovarian enlargement.

Q5: How do you confirm a malpositioned IUCD on imaging?

On ultrasound, malposition is suspected if the IUCD limbs are asymmetrical or if the device is not visualized in the uterine cavity. Radiographs are used to localize the device. CT is performed if the device is outside the uterus to assess for perforation.

Q6: What other pathologies should be considered when evaluating pelvic pain with ultrasound?

Besides gynecological causes, consider urological causes such as ureteric calculi and gastrointestinal causes like appendicitis. Therefore, scanning kidneys and right lower quadrant is often part of the ultrasound protocol.

Q7: How can ovarian vein thrombosis be detected on ultrasound?

Ovarian vein thrombosis is difficult to visualize on ultrasound due to limited visualization of adnexal veins. Look for a cord-like structure in the adnexa. CT or MRI is more reliable for diagnosis.