Cowden Syndrome: Comprehensive Imaging Guide and Clinical Overview

Overview

Cowden syndrome (CS) is a rare autosomal dominant disorder caused by germline mutations in the PTEN tumor suppressor gene. It was first described in 1963 and named after the family in which it was identified. CS is characterized by the development of multiple hamartomas affecting the skin, mucous membranes, brain, breast, thyroid, gastrointestinal tract, and other organs. Clinically, patients present with mucocutaneous lesions, macrocephaly, and an increased lifetime risk of malignancies, including breast, thyroid, kidney, and endometrial cancers. The disorder is part of the broader PTEN hamartoma tumor syndromes (PHTS) spectrum. Inheritance follows an autosomal dominant pattern with variable expressivity.

Key Imaging Features

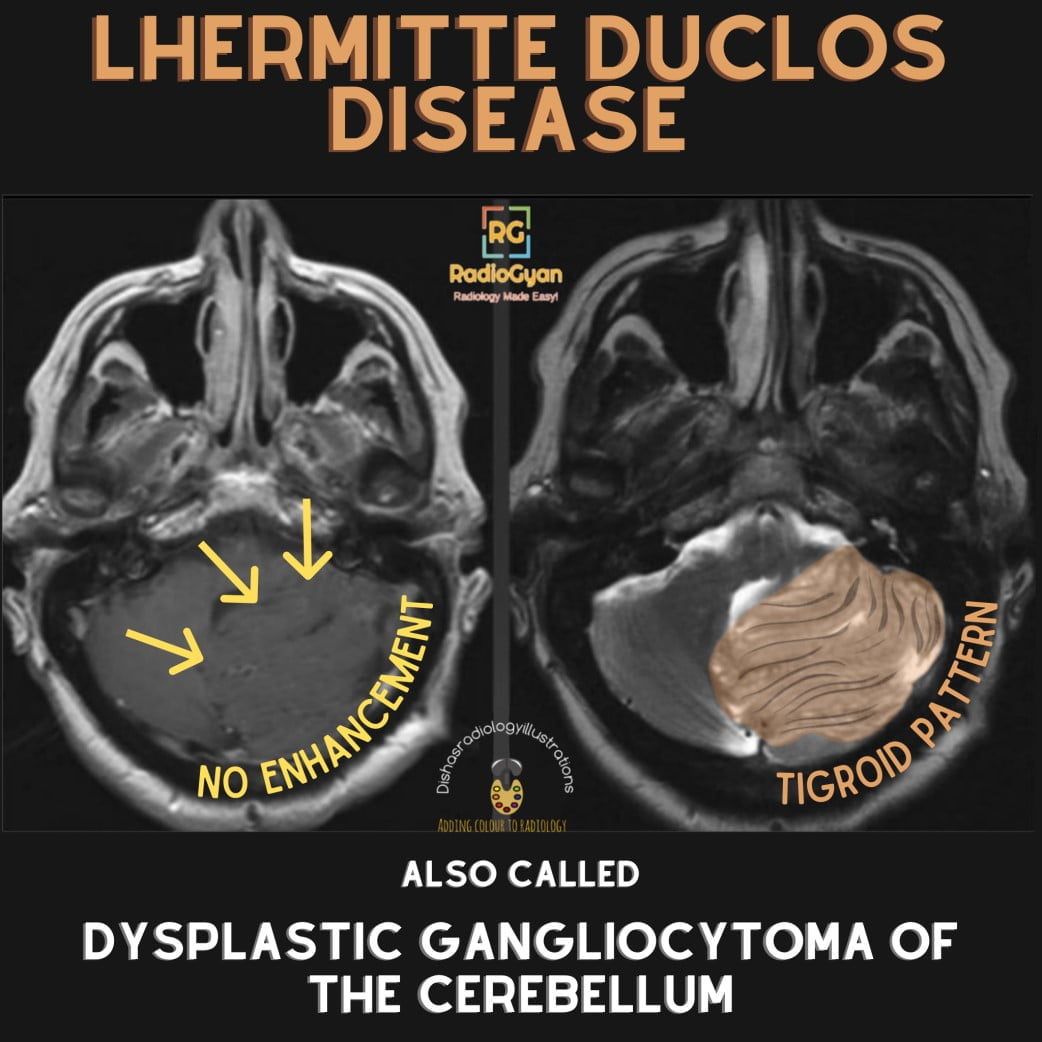

- Brain: Lhermitte-Duclos disease (dysplastic gangliocytoma) appears as a non-enhancing, gyriform, hyperintense mass on FLAIR and T2-weighted MRI in the cerebellum with characteristic “tigroid” striations.

- Breast: Multiple benign breast changes including papillomas, fibrocystic changes, and hamartomas; increased risk for breast carcinoma detectable on mammography, ultrasound, and MRI.

- Thyroid: Multinodular goiter and follicular adenomas are common; thyroid ultrasound often reveals multiple hypoechoic nodules, occasionally with suspicious features requiring biopsy.

- Gastrointestinal tract: Multiple hamartomatous polyps detectable on esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy; esophageal glycogenic acanthosis seen radiologically as multiple small plaques.

- Kidneys: Risk of renal cell carcinoma necessitates regular screening with renal ultrasound or CT.

- Other soft tissue lesions: Lipomas and vascular malformations appear as well-defined, noninfiltrative masses on CT or MRI; uterine fibroids and endometrial hyperplasia detectable with transvaginal ultrasound and MRI.

Pathophysiology

Cowden syndrome results from mutations in the PTEN gene, a crucial negative regulator of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway that controls cellular proliferation, apoptosis, and migration. Loss of functional PTEN leads to unchecked cellular growth and development of hamartomatous and neoplastic lesions in multiple tissues. The abnormal proliferation manifests on imaging as benign tumors and premalignant polyps or nodules across affected organs. For example, dysplastic gangliocytomas of the cerebellum (Lhermitte-Duclos disease) show hypertrophy and architectural distortion of cerebellar folia likely driven by abnormal neuronal growth pathways linked to faulty PTEN signaling.

Differential Diagnosis

- Multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndrome: Shares thyroid and breast cancer risks but lacks widespread hamartomas and characteristic mucocutaneous lesions seen in CS; imaging shows endocrine tumors rather than hamartomas.

- Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome: Another PHTS disorder with macrocephaly and hamartomas, distinguished by more prominent intestinal polyposis; imaging features overlap but clinical genetics differ.

- Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: Also presents with gastrointestinal hamartomatous polyps but with distinct mucocutaneous pigmentation; polyps often larger and more pedunculated on imaging.

- Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome: Predominantly associated with BRCA mutations, lacks the multisystem hamartomas and nonmalignant tumors typical of CS.

Imaging Protocols and Techniques

An effective approach to imaging in Cowden syndrome integrates multiple modalities tailored to organ-specific surveillance:

- Brain MRI: Use high-resolution T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences, preferably with 3D volumetric acquisitions, to identify Lhermitte-Duclos lesions. Regular imaging is advised if neurological symptoms develop.

- Breast imaging: Annual digital mammography combined with breast MRI with contrast is recommended starting at age 30–35 to detect early malignancy amidst benign hamartomas. Ultrasound guides biopsy of suspicious masses.

- Thyroid ultrasound: High-frequency probes should assess nodule characteristics regularly beginning in late adolescence. Elastography may aid in differentiating benign from malignant nodules.

- Gastrointestinal surveillance: Endoscopic examinations combined with targeted imaging such as contrast-enhanced CT or MR enterography help evaluate the extent and evolution of hamartomatous polyposis.

- Renal ultrasound or CT: Annual or biennial screening to detect early renal tumors; contrast-enhanced CT or MRI is useful for lesion characterization.

- Pelvic ultrasound and MRI: For female patients, transvaginal ultrasound and pelvic MRI assist in monitoring uterine fibroids, endometrial thickness, and potential malignancy.

Imaging pearls: Recognizing subtle findings such as esophageal glycogenic acanthosis plaques on upper GI imaging or detecting non-enhancing cerebellar mass with characteristic signal on MRI are key to early identification. Careful correlation with clinical and genetic findings prevents misdiagnosis. Repeat imaging should focus on growth or change in known lesions rather than isolated stable hamartomas. Pitfalls include confusing benign polyps with neoplastic lesions in the GI tract or misinterpreting benign breast hamartomas as malignancy.